The Southeast U.S. is one of the last parts of the country that lacks an integrated market for transmitting electricity across utility and state boundaries. A new study says changing that could save the region’s utilities and customers billions of dollars over the next two decades — and highlights that a currently proposed plan to create an energy-trading market encompassing the region’s dominant utilities likely won’t be enough to get the job done.

Tuesday’s report from think tank Energy Innovation shows that an integrated market could help utilities like Duke Energy, Southern Company and the federally operated Tennessee Valley Authority avoid overbuilding power plants, increase the efficiency of trading electricity between them, and introduce least-cost competition to the region’s vertically integrated regulatory regimes.

The analysis models out to 2040 the costs and economic and carbon impacts of creating an interstate grid operator for the states of Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina and Tennessee. Similar regional transmission organizations (RTOs) and independent system operators (ISOs) created two decades ago now manage the interstate transmission grids serving roughly two-thirds of the country, and they have yielded significant efficiencies by allowing utilities to share energy and reserve capacity across their regions.

Energy Innovation's analysis indicates the Southeast could also benefit greatly. Over 20 years, moving to an RTO model could yield $384 billion in economic savings, or about 19 percent compared to a “business-as-usual” case, and yield 2040 electricity rates about 29 percent lower than they’d otherwise be.

Energy-sector job growth could double, and the falling costs of clean power to replace the region’s coal and natural gas could drive the development of 131 gigawatts of clean energy — 52 gigawatts of solar, 42 gigawatts of wind and 37 gigawatts of energy storage — compared to just 21 gigawatts under the business-as-usual scenario, the model showed.

That could drive a 37 percent greater reduction in carbon emissions than the business-as-usual scenario — a worthwhile goal for utilities Duke and Southern that have pledges to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 and are seeking gigawatts of renewables over the coming years, said Michael O’Boyle, the think tank’s director of electricity policy.

In fact, the modeling conducted for Energy Innovation by Vibrant Clean Energy used these utilities’ existing integrated resource plans (IRPs) to yield their less-than-stellar results, he said. That indicates that failing to move toward a regional market could leave utilities “struggling to do it all on their own cost-effectively, and it could force them to use really expensive pathways.”

The Southeast's redundant capacity problem

O’Boyle cautioned that the modeling reflects an idealized RTO in which capacity, transmission and dispatch are all optimized for greatest efficiency. “There is more to the story in terms of supporting energy decarbonization goals,” such as state-by-state policies that could drive the shift from fossil fuels to renewables.

But there are some fairly obvious reasons why an integrated market would yield a more efficient system, he said. The main one is that, under the vertically integrated model, each utility will have to secure enough generation capacity to serve its own needs, rather than being able to share capacity with others across the region.

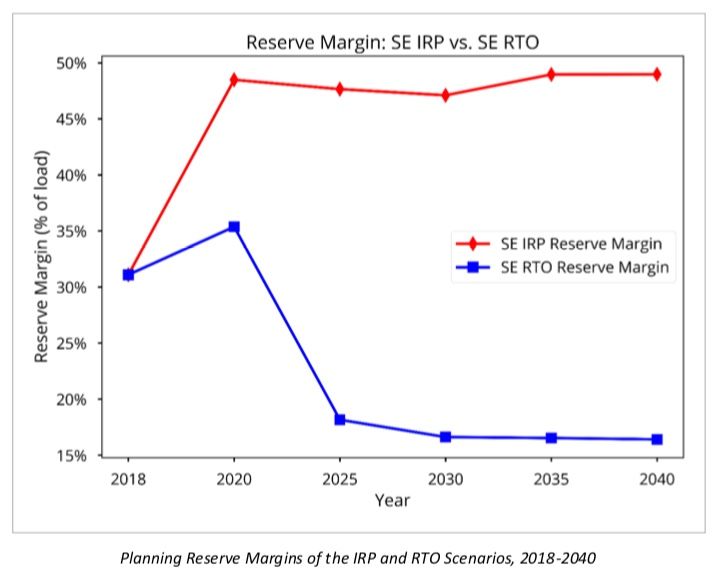

The modeling highlighted this discrepancy in the form of planning reserve margins, or the amount of generation required to meet peak grid demand in emergencies. Under the IRP scenario, that reserve margin could reach 48 percent — far greater than the 15 percent recommended by the North American Electric Reliability Corporation. Moving to an RTO model, by contrast, would yield a 16 percent margin, and with far less redundant capacity.

That problem can’t be solved simply by expanding real-time energy trading between the utilities, O’Boyle said. That’s the goal of the Southeast Energy Exchange Market, a proposal from the region’s major utilities that’s been in the works for months and publicly revealed in July.

“We did not endeavor to calculate the savings of [the Southeast Energy Exchange Market],” given the lack of details available on how it would work, O’Boyle said. But even if it does create a more efficient way to exchange electricity across the region as it’s generated, “without some form of resource-sharing, these IRPs will keep going in this obviously inefficient way.”

Forcing utilities to seek out new capacity through a competitive market structure that allows a multitude of resources, ranging from natural-gas-fired power plants to storage-backed renewables, to compete on cost and capability could drastically reduce the cost of meeting those future needs, said Taylor McNair, program manager at GridLab, a technical consultant that contributed to the report.

In fact, a separate analysis of an “economic IRP scenario” that presumed this least-cost approach to utilities’ existing plans indicated that it could yield about three-quarters of the cost improvements from the RTO scenario, he said.

Gauging the political realities

The carbon emissions improvements would not be as strong, however, at only one-third of the RTO scenario. That’s primarily because renewable energy’s growth will remain challenging without a more flexible and regionally coordinated system to balance the intermittency of wind and solar power through geographic diversity and a broader range of hydropower dams, new battery storage and other balancing resources.

Whether or not the Southeast will see an integrated market is an open question. Legislators in North and South Carolina have launched efforts to explore creating an RTO, driven by large power consumers seeking cheaper and cleaner electricity options than what are available from utilities today, said Bryn Baker, director of policy innovation for the Renewable Energy Buyers Alliance trade group.

But whether other states will join in this effort remains to be seen. Two decades ago, when the country's other ISOs and RTOs were formed, Southeast utilities failed to reach an agreement that would have created a similar structure. A report from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, which created and regulates ISOs and RTOs with its Order 2000, indicates the failure was due to unwillingness from the four different utility groups to align their separate market proposals into a unified structure.

What’s more, how an RTO is organized and governed will play a critical role in determining how effective it will be. A market controlled and operated by vertically integrated utilities is far less likely to impose competitive measures on its members than one controlled by an independent board of directors, for instance.

“Utilities have a clear interest in preserving their monopolies,” which allows them to pass the cost of new power plants, transmission lines and other capital investments on to their ratepayers, according to O'Boyle. “A push for independent oversight of a market should come from someone else, and policy stakeholders like FERC."